By: Sarah Pickard

When you enter the main hall of Imakumano Kannon-ji in Kyoto, one of the first things you will see is a butsudan, an altar commonly found in temples and homes in Japan. Its primary use is for paying respects to the Buddha and to any family members who have died. The altar is lined with bronze lanterns that are divided into sections that represent the five elements of Buddhist cosmology (earth, fire, air, water, and space).

The history of Imakumano Kannon-ji dates back to the Heian period (794 -1185), when Kukai (774-835), who was a Japanese Buddhist monk, calligrapher, and a poet who founded the esoteric Shingon school of Buddhism, was residing in the area. While he was practicing, he saw some unusual purple-looking clouds, so he followed them. The clouds then led him to where a man with white hair was sitting. The old man then told Kukai that he was the god Kumano, and he then gave Kukai a statue of Kannon. He then told Kukai that he needed to protect the place where he was standing. Kukai did as Kumano said and enshrined the statue in a hut which then later became known as Imakumano Kannon-ji.

Outside the hall, you will find a special statue of Kannon that was made for elderly people to pray for protection against senility (Boke Fuji Kannon = “Kannon to seal off senility”). The deity Kannon is one of the most popular deities in Japanese Buddhism. S/he can be found in both male and female forms. Kannon is the lord of compassion and goddess of mercy. One of Kannon’s’ job is to listen for prayers and cries of difficulty in the mortal realm and to help all who suffer achieve salvation. Kannon is also a bodhisattva, which means that s/he has achieved enlightenment but has postponed Buddhahood until all beings can be saved.

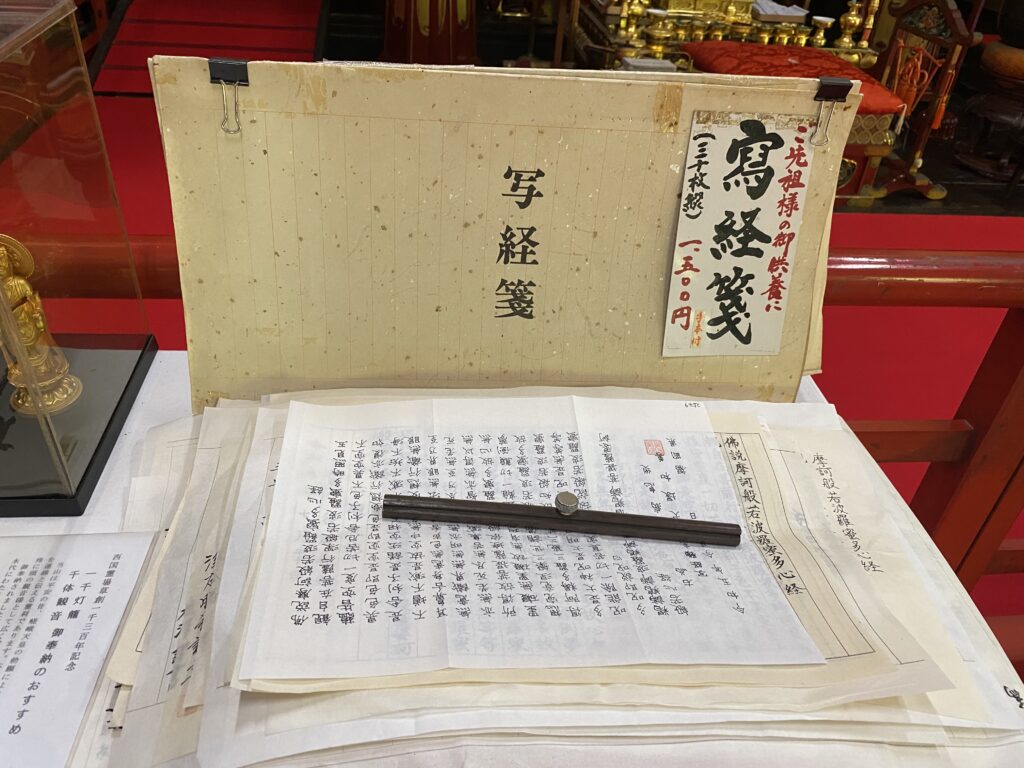

This temple is the 15th stop out of 33 stops of the Saigoku Kannon Pilgrimage route. When pilgrims stop here, they get a goshuin or a red stamp. While there, they stick a sticker called senjafuda onto the temple well to show that they have stopped at this temple during their pilgrimage.

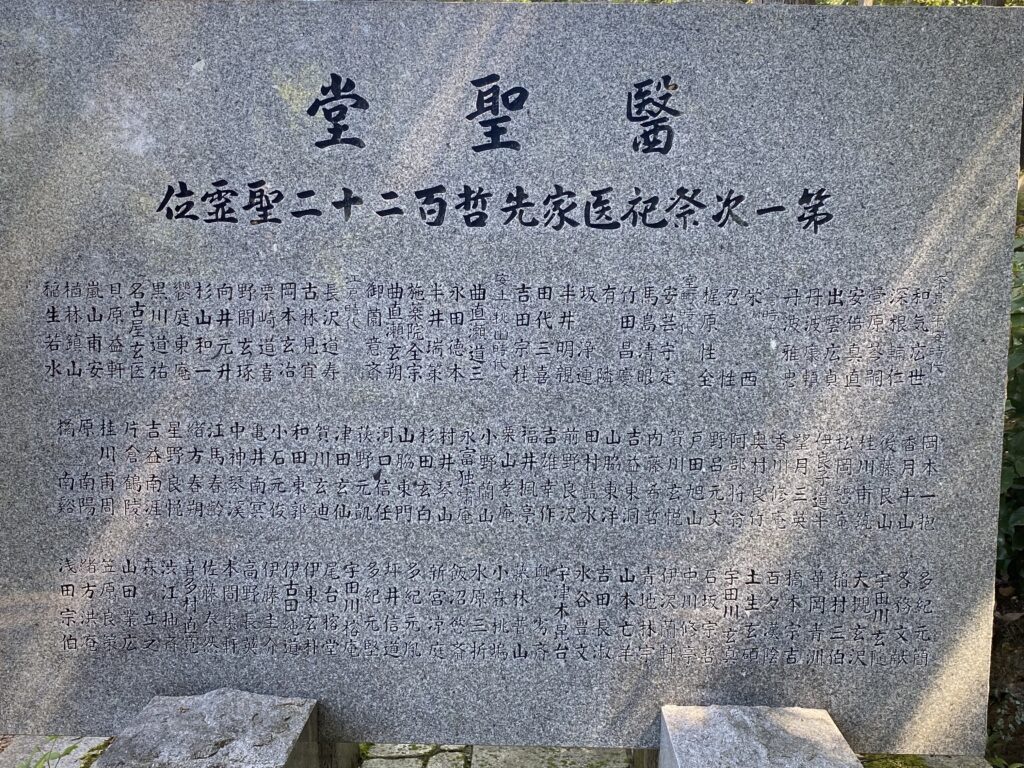

If you are a doctor, there is a specific pilgrimage route behind the temple for you to take that is said to empower one’s healing practice. This route is lined with images of Kannon, and you can stop to pray at any one of them if you want to. At the top of the circuit, there is a pagoda erected to commemorate the 1000th anniversary of the writing of the Ishimpo, which is the oldest surviving Japanese medical text. It was completed in 984 by Tamba Yasuyori and is 30 volumes in length. Just outside of the pagoda, there is a tablet that has a comprehensive list of the names of famous doctors from Japanese history.

Imakumano Kannon-ji regularly offers prayer rituals for longevity, general health, safe delivery of a child, prevention of senility, headaches, and many more health-related matters. Also, around the grounds of the temple, there are shrines for the Shinto spirits which show just how much Buddhism and Shinto are connected. Here, visitors can write a personal wish or prayer on a wooden plaque called an ema and leave it at the shrine to potentially be fulfilled.

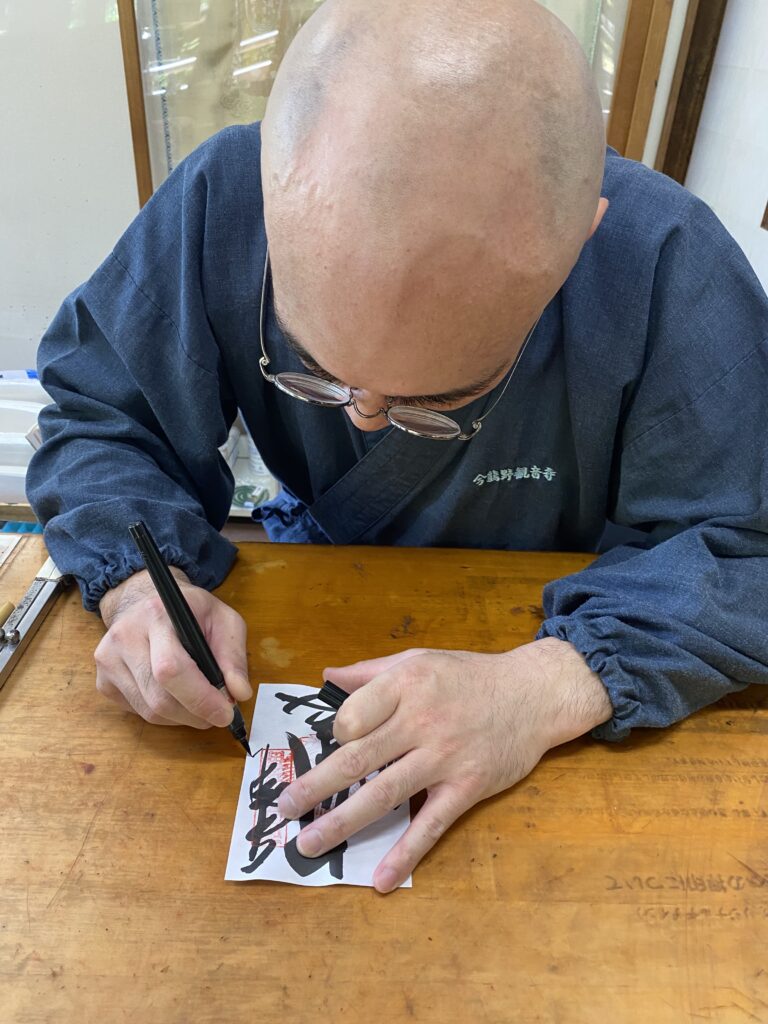

While inside the main hall, you can get a talisman made for your protection if you want to. Another service that is offered is the Hungry Ghost rite, which is a service and prayer that is performed to end the suffering of spirits and monsters who live in horrible torment and are afflicted with constant suffering.

The temple is also known for another medical purpose. This comes from the story of Emperor Goshirakawa, who went to the temple looking for a cure for his pounding headache. While he was there, Kannon appeared in his dreams and healed his headache by shining a light on his head. Ever since then, the temple has been known for curing headaches.

Media

VR Tour

Click here to view the accessible version of this interactive content

Scholarly Sources

- Triplett, Katja. Buddhism and Medicine in Japan: A Topical Survey (500-1600 CE) of a Complex Relationship, Berlin, Boston: De Gruyter, 2020. https://doi.org/10.1515/9783110576214

- Horton, Sarah J. “Shinto.” Macmillan Encyclopedia of Death and Dying, edited by Robert Kastenbaum, vol. 2, Macmillan Reference USA, 2002, pp. 763-765.

External Links

- Goshuin Yu, A. C. “Goshuin – Japanese Wiki Corpus.” Goshuin – Japanese Wiki Corpus, www.japanesewiki.com/history/Goshuin.html. Accessed 7 Oct. 2023. Wikipedia contributors. “Ishinpō.” Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia,15 May. 2023. Accessed 7 Oct. 2023.

- Schumacher, Mark. “Kannon Bodhisattva (Bosatsu).” Kannon Bodhisattva (Bosatsu) – Goddess of Mercy, One Who Hears Prayers of the World, Japanese Buddhism Art History, Accessed 7 Oct. 2023. https://www.onmarkproductions.com/html/kannon.shtml

- Wikipedia contributors. “Ofuda.” Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia, 10 Aug. 2023. Accessed 7 Oct. 2023.

- Wikipedia contributors. “Saigoku Kannon Pilgrimage.” Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia, 18 Jan. 2022. Accessed Oct. 2023.

- Wikipedia contributors. “Senjafuda.” Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia, 4 May. 2023. Accessed 7 Oct. 2023.

- Wikipedia contributors. “Hungry ghost.” Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia, 30 Sep. 2023. Accessed 7 Oct. 2023.

- Wikipedia contributors. “Ema (Shinto).” Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia, 13 Jun. 2023. Accessed 7 Oct. 2023.

- Wikipedia contributors. “Shinto Kami.” Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia, 27 Sept. 2023. Accessed 7 Oct 2023.