By Summer Nguyen

Introduced no later than the second century A.D., Buddhism has remained the primary religion in Vietnam. There are two main schools of Buddhism in Vietnam, Mahāyāna and Theravāda. Mahāyāna Buddhism is prevalent in northern Vietnam, where Chinese influences are more notable. Theravāda Buddhism persists in the south due to closer connections with Cambodia in the 19th century (Anh 1993, 111). Overall, modern Vietnamese society combines Confucianism, Daoism, Buddhism, Western values, and socialist values promoted by Vietnamese government (Nguyen 2016, 34).

Because of the Vietnamese Communist Party’s democratic socialist system, Vietnamese Buddhism developed in a fashion that situates the role of monks and nuns within the needs of the people (Nguyen 2016, 38). Due to the tight governmental control, the Vietnam Buddhist Sangha (Giáo hội Phật giáo Việt Nam, below VBS) is the only religious organization representing Buddhist monks and nuns in Vietnam (Hoa Sen Phật, 2018). With about 49,000 monastics and 17,376 temples and monasteries, the organization maintains an influential role in the field of medicine and healing. The VBS runs about 162 charity medical clinics (called Tuệ Tĩnh đường after the monk physician Thích Tuệ Tỉnh 慧靜禪師, 1330–1400), which provide access to healing in more remote regions of Vietnam. At these clinics, many of the medical practitioners are monks and nuns (Shuyin 2018). While keeping their monastic role, the monks and nuns live in the pagoda and work at the hospital (Shuyin 2018).

One of the most prominent groups of medical clinics under the VBS is run by Tuệ Tĩnh đường Hải Đức (TTDHD). Established in 1989, TTDHD operates four medical clinics in Huế Province that are supported by charity from laypeople. Using a combination of traditional and biomedicine approaches, TTDHD provides free medical care and treatment to over 200 patients a day across their four clinics, predominantly to local poor populations. These medical services include acupuncture, dermatology, internal medicine, obstetrics and gynecology, and otolaryngology. In recent years, TTDHD has charged a nominal fee for prescriptions due to increasing costs of Chinese imports. Of the 64 volunteer staff members, 18 of the medical practitioners are monks and nuns.

On top of treating patients in their four clinics, TTDHD established Hải Đức Community Support Centre in 2013 with the aim to encourage communities to both practice sustainable development and improve quality of life. The center fosters public education programs to spread awareness on topics such as environmental protection, human health, and gender equality. Hải Đức Community Support Centre also regularly organizes medical missions to more remote areas of the country, providing medical treatment and consultations for hundreds of patients each mission. In comparison to other temples around Vietnam with small, one-room clinics, TTDHD in Huế Province is much larger in size and scale of healthcare operations (Shuyin 2018).

Tuệ Tĩnh đường Hải Đức, like most free clinics in rural Vietnam, focuses on traditional medicine therapies (Thompson 2015, 13). Vietnamese traditional medicine has two main branches known as thuốc Nam (Southern medicine) from Vietnam and thuốc Bắc (Northern medicine) from China (Monnais, Thompson, and Wahlberg 2012, 133). Both kinds of medicine rely on external factors to explain disease and illness such as time of year, weather, food, or drink (Thompson 2015, 25, 59). Traditional practitioners avoid all surgical procedures and anything that involves cutting into the body. Traditional Vietnamese medicine heavily relies on herbology to treat illnesses (Thompson 2015, 86). Though both use many of the same ingredients, thuốc Bắc uses bats, snakes, donkeys, and other wild animals in their prescriptions while thuốc Nam uses very few animal parts (Thompson 2015, 99).

Media

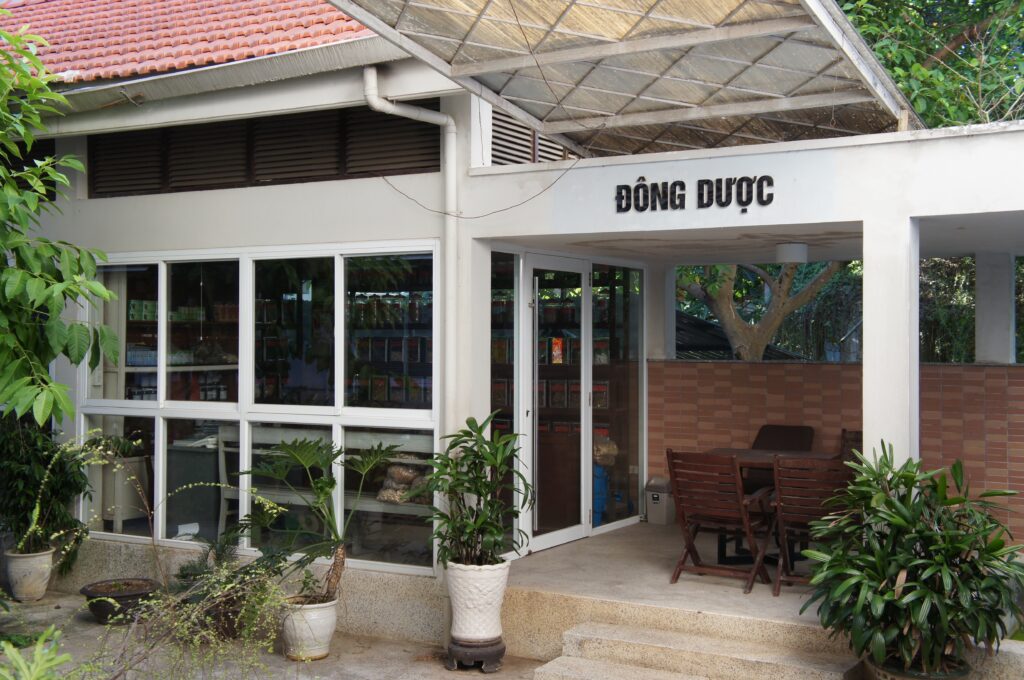

Exterior view of Tuệ Tĩnh đường Hải Đức (TTDHD).

The main entrance to Tuệ Tĩnh đường Hải Đức (TTDHD).

Interior view of the TTDHD herbal dispensary.

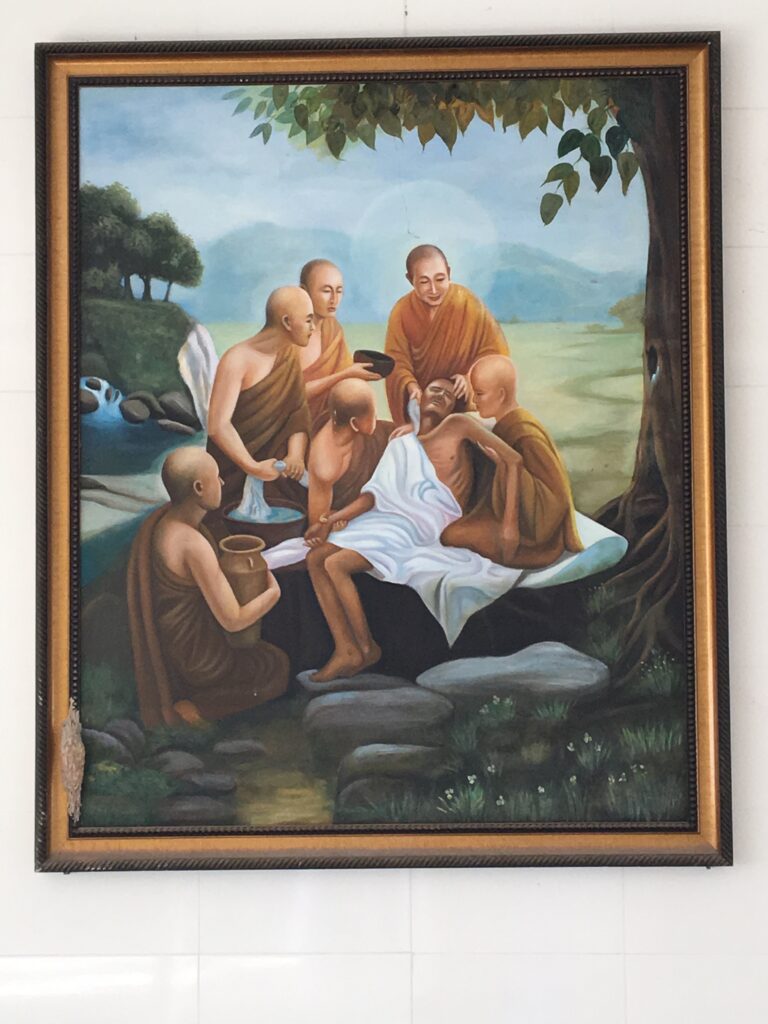

The depiction of a popular scripture story of Buddha caring for a monk with dysentery.

Scholarly Sources

- Anh, Nguyễn Thế. 1993. “Buddhism and Vietnamese Society throughout History.” South East Asia Research 1(1): 98–114.

- Monnais, Laurence, C. Michele Thompson, and Ayo Wahlberg. 2012. Southern Medicine for Southern People: Vietnamese Medicine in the Making. Newcastle upon Tyne: Cambridge Scholars Publishing.

- Nguyen, Quynh Thi Nhu. 2016. “The Vietnamese Values System: A Blend of Oriental, Western and Socialist Values.” International Education Studies 9(12): 32–40.

- Thompson, C. Michele. 2015. Vietnamese Traditional Medicine: A Social History. National University of Singapore Press.

External Links

- Phòng Khám Đa Khoa Từ Thiện Tuệ Tĩnh Đường Hải Đức. http://tuetinhduonghue.org.vn/

- Hoa Sen Phật. 2018. “Tuệ Tĩnh đường- những tu sĩ trang của Việt Nam.” Accessed June 23, 2021. https://hoasenphat.com/kien-thuc-phat-giao/tue-tinh-duong-nhung-tu-si-trang-cua-viet-nam.html.

- Shuyin. 2018. “Monastics in White: The Medical Monks and Nuns of Vietnam” Buddhistdoor Global. https://www.buddhistdoor.net/features/monastics-in-white-the-medical-monks-and-nuns-of-vietnam.